Home video was introduced to the world in august of 1965 by Sony with the Sony CV2400. Prior to the introduction of the CV2400, video was the domain of Professional Broadcasters. Video tape had only existed for about 10 years, and had only been in wide spread use since the late 1950s. Before Video Tape, all video signals were live broadcasts. Before the CV2400, the only option available for Home Movies was film. 8mm and 16mm film produced beautiful images, but shooting on film was expensive, slow, and cumbersome. It had to be developed, cut and spliced, and played back on a projector.

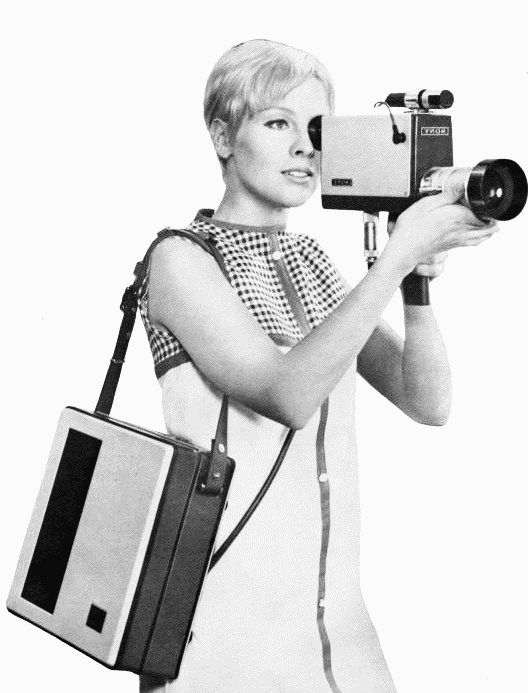

The Sony CV2400 changed all that, it was a Video Tape Player and Tape Recorder for home use. It was not portable, and the tapes it made could not really be played back on other VTRs because there was no way to adjust tracking. It was not a good product, it was not a useful product, and it was (most importantly) not a successful product but, it was a hell of a proof of concept and it was followed up in 1967 with the DV-2400 which included a portable camera and a portable Record-Only Video Tape Recorder. They called this the Video Rover.

The combination of a portable Video Camera and Tape Recorder meant that, for the first time, video could be used in many of the same ways as film for home users. Video looked worse than film, but it had a few points going for it that made it Very attractive when compared to film:

- Immediacy – Things shot on video could be played back the same day! While the DV-2400 did not do playback, a tape could be removed from the DV-2400 and inserted in to the CV-2400 immediately (and even that step would be rendered obsolete in future products) compared to the weeks or months it took to get film developed.

- Price – Video tape cost a lot less than film, could be reused if a shot didn’t work out, and didn’t require the extra expense of developing film. You could shoot a lot more video than you could film.

- Runtime – The most common film camera of the 1960s was a mechanical affair, which would run for 30 seconds at a stretch (and it couldn’t even record sound!) These early video cameras boasted a battery life in the 45 minute range, and a record time of roughly half an hour per tape.

- Sound – While it was not impossible to have sound on 8mm or 16mm film, it was remarkably uncommon in the home-movie market. Video cameras enabled Sounds and Pictures at the same time. It seems simple today, but this shifted what it was possible to create outside of a professional setting.

The DV-2400 was followed up with the AV-3400 / AVC-3400, which used the EIAJ-1 standard for cable connections between the camera and other devices, (which standardized the EIAJ-1 standard, in fact) and introduced modern conveniences like tracking control, and the ability to record and play back from a single portable unit, which could be connected directly to a television. The standardization of cables and connectors meant that the AVC-3400 could also be used with video mixers, other video tape recorders, other cameras, etc. It meant that Video Gear could be reasonable assured of inter-operation, even when using devices from multiple manufacturers.

This combination of equipment came to be known as a PortaPak. It recorded for half an hour per tape, and would run for 45 minutes on its battery pack. The footage was fine, not remarkable, but usable.

It was relatively affordable, relatively accessible, and way cheaper than shooting on film for any given production. It enabled people to create video and distribute it on a scale that had previously been impossible and, for the first time in the history of television, it appeared poised to transform the Read Only medium in to a Read/Write medium.

It was still not perfect, it still had some problems, some significant, but it worked, and it sparked a revolution.

In many ways, that revolution was most visible with the publication of 1971’s Guerrilla Television, and it is after that text that I have named this section of our history lesson. There’s a lot more to say about Guerrilla Television, and the other early video movements, than could reasonably fit in this text. Perhaps one day I will write a book. In the meantime, I will summarize:

The key principles of Guerrilla Television can be summarized as:

- Television is the means by which people come to understand themselves and one another

- Shoot video of things as they happen, don’t try and stage a shot or make a movie. It’s video vérité – video shot and edited as to provide candid realism – edit as little as possible, don’t editorialize.

- Traditional Television is a beast that must be slain in order for our society to be healthy.

Out of this concept of Guerrilla Television, a large number of different groups of video producers sprung up. For our purposes, we will examine three of them and explore the ways they approached the transformative power of DIY TV.

New York

The most often talked about groups in the DIY Media scene in New York in the late 60s and the early 70s were the Videofreex, the Raindance Foundation, and Metropolis. We’ll touch briefly on Raindance and Metropolis, but the it is the successes and failures of the Videofreex where we’ll spend the most time.

The Videofreex were born out of Woodstock. While Michael Wadleigh and his scores of filmographers were shooting the stage at Woodstock, a bunch of attendees were walking around with new PortaPaks (and, occasionally weirder video gear) documenting what things were like on the ground for the attendees. Several of these videographers exchanged information and got together after the concert to see what kinds of trouble they could make.

Officially, they became The Videofreex when they were approached by CBS executive Don West to shoot a video vérité television show about the American counterculture movement (or, to put it another way, they had been hired to point their cameras at things that were happening, and not to edit them too much.) This put them in touch with people like Abbie Hoffman, Fred Hampton, and others, and it resulted in some incredible footage.

CBS, of course, never broadcast the program, and intended to bin it. The ‘freex liberated their own tapes, and many are available online today. See the documentary Here Come the Videofreex or the book Subject to Change: Guerrilla Television Revisited for more information on the formation of the crew and their work with CBS.

Also in NY, a group calling themselves Metropolis was working with Manhattan’s public access television network (a predecessor to MNN, the current Manhattan public access network, and the birthplace of some of the most interesting DIY TV of the last 20 years) to shoot concerts at CBGBs. They produced professional looking and sounding footage of incredible concerts, and they distributed them on Television.

While Metropolis was documenting the music scene and the ‘freex were working with, and being disappointed by CBS, the Raindance Foundation was busy working on Radical Software, the magazine of record for the video counter culture. They were heavily influenced and inspired by Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog, Buckminster Fuller’s Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, and the works of Marshall McLuhan. These influences are all over the works that Raindance produced, for better and worse. From this group eventually emerged the handbook for the first video revolution: Guerrilla Television. At their heart was the idea that traditional broadcasting was a scourge that must be eradicated through the judicious application of DIY Video.

Metropolis had distribution. Raindance had a publication. The ‘freex had the rug pulled out from under them by CBS. As a result, they took the message of the Raindance Foundation to it’s logical extreme. They re-branded as The Media Bus, received a 40,000 dollar grant from the state of New York, and moved to a 27 bedroom house in the Catskills where they used a television transmitter “procured” for them by Abbie Hoffman (member of the Chicago 7, author of steal this book, sometime fugitive from the FBI) to start the nations first Pirate Television station.

The Videofreex spent the next several years broadcasting from Lanesville, NY, attempting to create a kind of participatory media, in which the residents of their small town became a part of the broadcasts. Through Lanesville TV they pioneered techniques such as eye-witness news, and they built a community. Eventually, they were shut down by changes in FCC regulation and enforcement.

Members of the Videofreex went on to join TVTV (see California, below), to work as artists and activists, and to occasionally produce more traditional media. The Videofreex Archive, containing more than 1,500 original tapes, is housed at the Video Data Bank, operated by the Art Institute of Chicago. Much of the archive has been digitized, and some of it is slowly being made available to the public.

California

After writing in Guerrilla Television that traditional broadcast media was the enemy, “The Beast”, which must be destroyed for the good of the human race, Michael Shamburg (along with Skip Blumberg, and with frequent assistance from other members of the Videofreex) moved to San Fransisco and started making documentaries intended for distribution on traditional television.

This was, of course, entirely at odds with their professed values and beliefs and also the best option available to them. Shamburg, in Guerrilla Television, proposed a theory of the Ecology of the Videosphere, and lamented the lack of ecological diversity. In Radical Software, Shamburg and other members of The Raindance Foundation indicated that they genuinely believed that the FCC was going to enable a distribution mechanism for DIY Video, and their statements about the evils of traditional television as a distribution mechanism were written with that idea at their heart.

Nixon, of course, would do no such thing. Faced with the option to 1) make videos no one would see outside of gallery exhibits, on the single pirate television network in the country, and through mail order catalogs or 2) make videos that would be seen by thousands or tens of thousands of people on traditional television, Shamburg and some others from the NY movement chose distribution.

They founded Top Value Television, or TVTV, which produced dozens of award winning documentaries and, throughout the 1970s, proved to be a major force for social and political commentary in this country. Their work is magnificent: it’s produced in a style that was entirely alien to the production techniques of the major players in television in the 60s and 70s. It is disarming, moving, and occasionally deeply unsettling.

The group lasted the longest of any of the video collectives of the 70s, but ultimately fell apart as a result of interpersonal conflict and an ever shrinking supply of funding for the arts.

Shamburg went on to form a production company and has served as the producer on numerous major Hollywood films. He was, in many ways, subsumed in to The Beast he believed he was fighting, but the work he created and/or enabled through TVTV continues to shine as an example of the transformative and potentially revolutionary power of video, and the things he and his compatriots wrote in Guerrilla Television and Radical Software form the ideological starting point for this ongoing exploration of the potential transformative power of Television in the modern era.

Appalachia

Insulated from the counterculture movement of the 1960s, and separate from the video collectives of NY and CA, southern Appalachia had their own radical, DIY television movement in the form of Broadside TV.

Broadside TV was a Tennessee based group of Grassroots Video producers working to create local content for the Appalachian region, in the folk school tradition. They were able to operate thanks to the fact that Television was exceptionally difficult to broadcast in the hills of Appalachia, so cable TV was the only way most Appalachians were able to access television. The TVA connected many homes to a cable service, and cable services were required, by FCC mandate, to broadcast at least some Locally Originating material.

Broadside TV stepped in and provided this locally originating material to various Cable operators throughout TN, in exchange for some funding which they used to produce video vérité style documentary footage and explorations of life in Appalachia throughout the region. They would drive from holler to holler exhibiting their work-in-progress footage to the residents of each community they entered, before then asking those residents to contribute their own thoughts on the topic du jour.

Along the way, they also taught people how to produce their own video, provided equipment to under-served communities, and generally did Good Work in an impoverished and unfairly maligned region of the US. Their videos were instrumental in helping Congress decide how to regulate strip mining in the US (see “Appalachian Perspective”” from the Media Burn Archives.)

Ultimately, Broadside TV’s success may have been it’s undoing. Shortly after their video was used in a Congressional hearing, the FCC under Richard Nixon changed the rules around locally-originating programming. Whether or not this was an intentional attack on Broadside TV, or a less targeted attack aimed at shutting down independent thought more generally, it had the impact of cutting off the major source of funding and the only avenue of distribution available to Broadside TV, and ultimately resulted in their closure.

Successes

The successes of the early DIY TV movement can be largely grouped in to two categories: Theoretical and Practical. From a theoretical standpoint, the Raindance Foundation gave us a framework for exploring independent video through the concept of the ecology of the videosphere, a framework which we can extend to build our new DIY TV movement.

From a practical standpoint, these early video collectives gave us Video:

- The Videofreex interviewed Fred Hampton weeks before the Chicago Police Department murdered him in his own bed, and their conversation presents Fred at his most candid and revolutionary.

- Broadside TV produced documentaries that shaped Congressional hearings and transformed Appalachia

- Lanesville TV pioneered the concept of eye witness news, and built the first truly participatory media landscape

- TVTV revealed corruption in the Democratic National Convention, took down a cult leader, and exposed the ugly underbelly of American politics.

And that’s just the tip of a deep iceburg. See “Further Watching” for more.

Failures

The biggest contributors to the failure of each of these video collectives came down to distribution and funding, and these twin issues fed on one another. If no one is watching, no one is paying. If no one is paying, nothing new is made. If nothing new is made, there’s nothing to watch.

The distribution problem was a technical problem, which has since been obviated in ways that we will discuss later in this text. The spectre of funding still hangs over the DIY media movement, but things are not nearly as dire as they were when the video collectives of the 1970s began to implode.

These early video organizations were also entirely preoccupied with Telling The Truth, with speaking truth to power, with “realizing the potential of video as the driving force of technoanarchy” or whatever other vague sci-fi technobable they could muster. They were not, usually, concerned with producing entertainment. This was a major failure, because it meant that they spent most of their time talking to people who already agreed with them. (This was not a universal fact: Metropolis, the Videofreex, and Lanesville TV all produced some entertainment, and some of their most successful tapes were intended as entertainment first and sometimes only as entertainment –Talking Heads at CBGBs, Mountain at the NY Pop Festival, the UFO sighting for Lanesville TV– but entertainment was secondary to education, and that limited their potential reach.)

But (possibly more importantly) these organizations also failed as a result of internal contradictions within their worldviews that resulted in an inability to effectively center their values in their work. Guerrilla Television strove to be apolitical, and in doing so they did themselves a disservice. They pursued an individualist approach to solving a problem which will only ever be solved through collective action. They built a culture in which individuals were elevated above their peers, even as they also worked collectively to implement their solutions. They recognized that the union makes us strong, but they let individual choices and big personalities get in the way of that union.

This internal contradiction, the struggle between collectivism and individual expression, was at the heart of the failures of many of the “opt-out” sects of the 60s and 70s counterculture. Individualist libertarian ideals are incompatible with building a revolutionary society that can sustain and outlive the individuals within the movement.

It is not enough for any one person to remove themselves from the influence of mass media. This is not Walden. We are not dropping out. We must, together, build a new path forward for as many people as want to participate.

We are, and must be, politically minded even as we tell stories that are largely apolitical. We will revisit this idea in the Jamming the Media section later in this text.

Further reading

I strongly suggest that anyone interested in this formative period in the DIY TV movement track down digital copies of the Raindance Foundation’s Radical Software, a zine that they published throughout the 1970s. The book Guerrilla Television itself has some interesting things to say, but not enough interesting things to justify the prices that it commands today. If you can find a copy through your local library or check out a digital copy from the Internet Archive, it is an interesting work, but Radical Software is more generally applicable today.

The 1997 text Subject to Change: Guerrilla Television Revisited serves as retrospective an analysis of the movement written and published months before internet video would again transform the landscape of DIY Media. It paints the picture of a failed movement of idealists who compromised or were compromised, but it is the best text on the subject available today.

A few other books, and a few documentaries have also been published in recent years. I have not read all of them yet although this is a living document, I’ll amend it as I read them.

Further Watching

These people weren’t writers, they were video producers. I recommend looking for the following videos:

- Lanesville TV UFO Sighting on Archive.org and Mountain Town Video

- Lanesville TV News Report

- Videofreex interview Fred Hampton

- Videofreex Mountain in concert

- Metropolis Talking Heads at CBGBs

- Videofreex Mayday Realtime

- TVTV The world’s Largest Television Studio

- TVTV Lord of the Universe

- Broadside TV – The Appalachian Perspective – From the Mediaburn Archive

- Any material from Broadside TV that you are able to access (The university of Eeast Tennessee has digitized the majority of their collection, held in the Archives of Appalachia, and will allow access to individual items over the internet by request. This is a Huge pain in the ass, but it is worthwhile to see the techniques this group employed)

More recent Documentary coverage:

- “Here come the Videofreex” is a documentary about their movement

- “TVTV: Video Revolutionaries” was released in 2018 and chronicles the rise and fall of TVTV

- “Videofreex Pirate Television” is a web distributed documentary and an assemblage of clips from the Lanesville TV broadcasts

Archive.org, the Media Burn archive, and the Video DataBank all have large collections of work from these early video pioneers. Some of this work is freely available, while other parts of this work are very difficult or expensive to obtain.

If you struggle to find any of the above videos, or would like further suggestions, I can be reached @ajroach42@retro.social.

Up Next: Shot On Video